History Of Lebanon

"Where It All Began"

Phoenician Era (circa 3000–539 BCE)

Lebanon’s earliest recorded civilization was that of the Phoenicians, a Semitic people who settled along the narrow coastal strip of the eastern Mediterranean. The Phoenicians were not a unified nation but rather a collection of independent city-states, including Byblos, Sidon, Tyre, and Arados. These cities flourished thanks to maritime trade, shipbuilding, and craftsmanship, especially in purple dye, glass, and timber from Lebanon’s famous cedar forests.

Phoenician sailors and merchants established trade networks and colonies across the Mediterranean, notably Carthage in present-day Tunisia. Their most enduring legacy is the alphabet, which influenced Greek and Latin scripts and ultimately modern alphabets worldwide.

Persian and Hellenistic Periods (539–64 BCE)

In 539 BCE, Lebanon fell under the rule of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, which allowed the Phoenician cities considerable autonomy as long as they paid tribute and contributed ships to the Persian navy. Following Alexander the Great’s conquest in 332 BCE, the region became part of the Hellenistic world. Hellenization introduced Greek language and culture, blending with native traditions and contributing to Lebanon’s long history as a crossroads of civilizations.

Roman and Byzantine Periods (64 BCE–636 CE)

The Romans annexed the region in 64 BCE, and under their rule, cities like Berytus (Beirut) prospered. Beirut became renowned for its law school, one of the most famous in the Roman Empire. Roman architecture, roads, and temples (such as those at Baalbek) still stand today as evidence of this era’s grandeur.

After the division of the Roman Empire, Lebanon became part of the Byzantine Empire, during which Christianity spread widely, particularly among the Maronites, who took refuge in Mount Lebanon.

Islamic Caliphates and Medieval Lebanon (636–1516)

Arab Muslim forces conquered Lebanon in the 7th century, integrating it into the Umayyad and later Abbasid Caliphates. The region’s mountainous terrain allowed various communities, including Maronites, Druze, and Shiites, to maintain distinct identities and enjoy relative autonomy.

During the Crusades (1099–1291), parts of Lebanon came under Crusader control, but ultimately fell back to Muslim rulers, first the Mamluks and later the Ottomans.

Ottoman Era (1516–1918)

Under Ottoman rule, Lebanon was part of the province of Syria but enjoyed semi-autonomous status, especially in Mount Lebanon, governed by local emirs like the Maans and Shihabs. The region was characterized by its religious diversity and occasional sectarian strife.

The 19th century witnessed increasing European interest and intervention, often under the pretext of protecting Christian minorities. The most notable crisis occurred in 1860, when clashes between Maronites and Druze led to massacres and international intervention, resulting in a new administrative arrangement for Mount Lebanon.

French Mandate and Independence (1918–1946)

After World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Lebanon came under French mandate (1920) as part of the partition of Ottoman territories. The French expanded Lebanon’s borders to create Greater Lebanon, incorporating Muslim-majority areas alongside Mount Lebanon.

Lebanon declared independence in 1943, adopting the National Pact, an unwritten agreement distributing power among the country’s religious communities. Full independence came in 1946 with the withdrawal of French troops.

Post-Independence Lebanon and the Civil War (1946–1990)

The early decades of independence saw Lebanon thrive economically and culturally, with Beirut emerging as a center of finance, education, and tourism. However, underlying sectarian tensions, regional conflicts (especially the Palestinian question), and demographic imbalances led to political instability.

In 1975, civil war erupted, pitting various sectarian militias, Palestinian factions, and foreign powers (including Syria and Israel) against each other. The war lasted 15 years, devastating the country and killing over 100,000 people. The Taif Agreement (1989) ended the conflict and restructured the political system to provide more balanced representation.

Lebanon Since 1990

Post-war Lebanon focused on reconstruction, led initially by Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. However, the country faced continued challenges: Syrian military presence (which ended in 2005 after the assassination of Hariri), the 2006 war with Israel, political paralysis, and a deepening economic crisis that came to a head in 2019 with mass protests.

The 2020 Beirut port explosion symbolized the depth of state dysfunction, prompting calls for systemic reform. Today, Lebanon grapples with political deadlock, economic collapse, and the resilience of its people in the face of adversity.

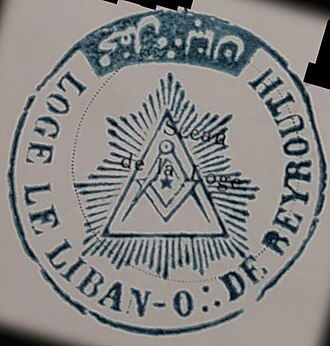

Freemasonry in Lebanon

Freemasonry in Lebanon has a rich history, with its origins tracing back to the mid-19th century.

Beginnings and Early Influences:

The first regular Masonic lodge in Lebanon, Palestine Lodge No. 415, was chartered on May 6, 1861, by the Grand Lodge of Scotland. This lodge operated in Beirut and primarily conducted its meetings in French. Other lodges soon followed, with the Grand Orient of France chartering a lodge in 1869 that worked in Arabic. Freemasonry was introduced to Lebanon and Syria around 1860, partly through lodges connected to the National Grand Lodge of Egypt. The presence of Algerian Emir Abdel Kader el Jazaïry in Syria, who was initiated into Freemasonry in Paris in 1864, also brought the fraternity to public notice in the region. Over time, various Grand Lodges established a presence in Lebanon, including those from France, Scotland, Italy, America, and Egypt. By the early 20th century, Freemasonry had expanded significantly, with lodges operating under the Grand Orient of France (known for progressive thought), the United Grand Lodge of England (promoting traditional rituals), and the Grand Lodge of Scotland.

Societal Role and Notable Figures:

Freemasonry attracted intellectuals, professionals, and businessmen who were drawn to its values of integrity, brotherhood, and intellectual pursuit. Lodges served as vibrant salons, fostering discussions on literature, philosophy, and the arts, thereby enriching Lebanon's cultural landscape. During Lebanon's path to independence from the Ottoman Empire and later the French Mandate, Freemasons became influential members of the nationalist cause. They advocated for political change, promoted harmony among diverse Lebanese communities, and contributed significantly to the intellectual and cultural debates that shaped the young nation. Notable Lebanese figures, such as the poet and philosopher Khalil Gibran and Lebanon's first president, Bechara El Khoury, were involved in Freemasonry.

Challenges and Resilience:

Freemasonry in Lebanon faced periods of challenge and dormancy. Some early lodges did not survive the First World War. During the Lebanese Civil War, most lodges became dormant, though some, like the Syrio-American Lodge, continued to meet intermittently, providing a space for communication and understanding amidst the conflict. After the civil war, Freemasonry experienced a revival in the 1990s, with lodges resuming activities and new generations of Masons continuing the traditions.

Current Status:

Today, Freemasonry remains active in Lebanon, with lodges operating across the country under various Masonic jurisdictions. There are four recognized and regular jurisdictions, alongside a number of clandestine and irregular lodges.